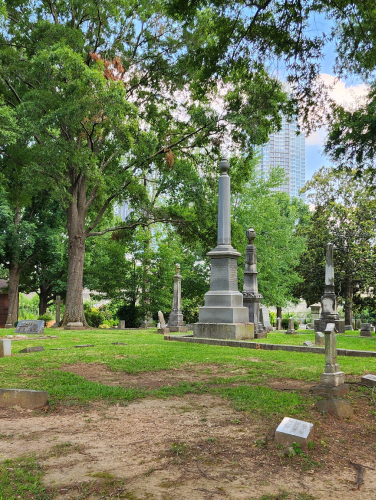

Elmwood/Pinewood Cemetery

)ca. 1853)

For more than a century, Charlotte’s second municipal cemetery evidenced how segregation was more than a matter of daily life in the Queen City.

700 W. 6th St., Charlotte, NC 28202

By the mid-1850s, Settlers’ Cemetery on West Fifth Street – Charlotte’s first and only municipal burial ground – was rapidly reaching its capacity. In 1853, the city purchased the first of several tracts of land totaling 100 acres for a new municipal cemetery. Given race relations of that era, the property developed as three distinct but adjacent cemeteries: Elmwood (for the burial of White persons), Pinewood (for the burial of Black persons), and Potter’s Field (for the burial of White paupers). Designed as a completely separate burial ground, Pinewood was inaccessible by Elmwood’s main Sixth Street entrance. Pinewood’s separate Ninth Street entrance and its lack of both paved streets and peripheral fencing (until the mid-twentieth century) evidenced the city’s system of strict racial segregation, further underscored in the 1930s by the erection of a fence between Pinewood and Elmwood.

Property Quick Links

Whereas Settlers’ Cemetery contains the remains of Charlotte’s founding settlers, Elmwood is the resting place of Charlotte’s New South pioneers, led by industrialist Daniel A. Tompkins and developer Edward Dilworth Latta. Political leaders buried in Elmwood include North Carolina governor Cameron Morrison, former Charlotte mayors S. S. McNinch and Phillip Lance Van Every (also founder of Lance, Inc.), and U.S. senator John Motley Morehead. Other notable Elmwood internments include Dr. Annie Alexander (the South’s first female physician), Harriet Abigail Morrison Irwin (the first woman to practice architecture in North Carolina), film actor Randolph Scott, William Henry Belk (co-founder of Belk department stores), and architect William H. Peeps. Elmwood’s first burial, in 1855, was reportedly a child of William Beattie.

Likewise, many of Charlotte’s prominent Black citizens are interred at Pinewood, including Dr. John T. Williams (one of North Carolina’s first three Black doctors and consul to Sierra Leone), A.M.E. Zion Bishop Thomas H. Lomax, Lt. Col. C.S.L.A. Taylor (Charlotte's first Black firefighter and the highest ranking Black officer in the Spanish-American War), businessman and founder of several civic institutions for the Black community Thad Lincoln Tate, and Caesar Blake (Imperial Potentate of the Ancient Egyptian Arabic Order and leader of Negro Shriners throughout the 1920s). The Smith Mausoleum, containing the remains of Charlotte’s first Black architect William W. Smith, resembles one of his most notable works, the Mecklenburg Investment Company building (still located at Brevard and Third Streets). The grandparents of renowned artist Romare Bearden are also buried in Pinewood.

Finally, in the late 1960s, empowered by the successes of the civil rights movement, Black Charlotteans – led by Fred Alexander, Charlotte’s first black city councilman – began a crusade to bring down the fence that separated Pinewood and Elmwood. For much of 1968, Alexander pushed City Council’s White majority opposition to remove the fence. Finally, in January 1969, Mayor Stan R. Brookshire broke the stalemate. The fence was removed the following day by the Mecklenburg Jaycees, a service organization for Black youth. After more than a century of segregation, Charlotte’s second municipal cemetery finally became a single burial ground.